14th & 15th Amendments Of U.S. Constitution Protect Canada's Teck Resources From Cuba Libertad Act Lawsuit. No "Personal Jurisdiction" For U.S. Courts.

/HEREDEROS DE ROBERTO GOMEZ CABRERA, LLC v. TECK RESOURCES LIMITED [1:20-cv-21630; Southern Florida District]

Hirzel Dreyfuss & Dempsey, PLLC (plaintiff)

Roig & Villarreal, P.A. (plaintiff)

Law Office of David A. Villarreal, P.A. (plaintiff)

Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman (defendant)

Oral argument held this date. Oral Argument presented by Leon Francisco Hirzel, IV for Appellant Herederos De Roberto Gomez Cabrera, LLC and Robert Sills for Appellee Teck Resources Limited. [Entered: 06/07/2022 02:04 PM]

Opinion issued by court as to Appellant Herederos De Roberto Gomez Cabrera, LLC. Decision: Affirmed. Opinion type: Published. Opinion method: Signed. The opinion is also available through the Court's Opinions page at this link http://www.ca11.uscourts.gov/opinions. [Entered: 08/12/2022 09:53 AM]

Judgment entered as to Appellant Herederos De Roberto Gomez Cabrera, LLC. [Entered: 08/12/2022 09:56 AM]

LINK To Opinion of the Court (8/12/22)

LINK To Libertad Act Lawsuit Filing Statistics

Excerpts from Opinion:

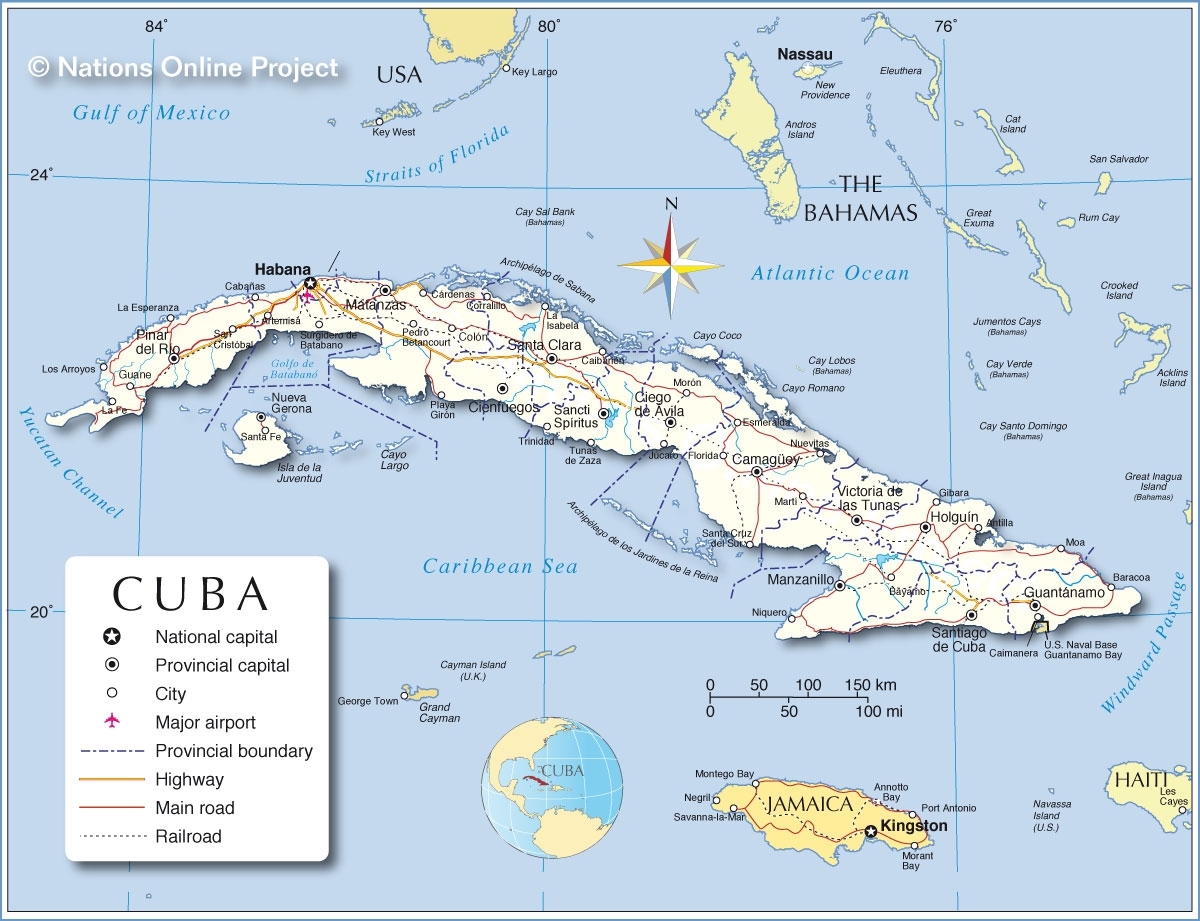

In 1960, the revolutionary Cuban government confiscated Roberto Gomez Cabrera’s mineral mines. Cabrera’s children, who inherited his claim to the mines, allege that Teck, a Canadian cor poration, managed the mines and thereby “traffic[ked]” in them in violation of the Helms-Burton Act.

Cabrera’s children assigned their claims to a Florida LLC, Herederos de Roberto Gomez Cabrera, and Herederos sued Teck under the Helms-Burton Act in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida. Broadly speaking, the Act imposes li ability on “any person” who “traffics in property which was confis cated by the Cuban Government on or after January 1, 1959.” 22 U.S.C. § 6082. Teck moved to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdic tion. The district court granted Teck’s motion, holding that Flor ida’s long-arm statute didn’t provide jurisdiction over Teck and, additionally, that Teck lacked the necessary connection to the United States to establish personal jurisdiction under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4(k)(2). For the reasons explained below, we agree with the district court.

The parties here agree that Rule 4(k)(2)’s first condition applies—Teck isn’t “subject to jurisdiction in any state’s courts of general jurisdiction.” Accordingly, we must decide whether exer cising personal jurisdiction here would be “consistent with the . . . Constitution.” For purposes of this case, the relevant constitu tional provision—and we flag this issue because it gets to the nub of the parties’ dispute—is the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, which applies to the federal government and its courts, not the Fourteenth’s, which applies to the states.

Despite their agreement that the Fifth Amendment governs the personal-jurisdiction inquiry here, Herederos and Teck ad vance competing jurisdictional analyses. For its part, Teck con tends that we should analyze personal jurisdiction under the Fifth Amendment the same way we would under the Fourteenth Amendment—i.e., ask whether the defendant has sufficient “mini mum contacts” with the forum and whether “maintenance of the suit [would] offend ‘traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.’” Int’l Shoe Co. v. Wash., 326 U.S. 310, 316 (1945). Here deros, by contrast, urges us to apply a more lenient “arbitrary or fundamentally unfair” standard that we have sometimes used in what it calls “extraterritorial jurisdiction” cases. See Br. of Appel lant at 15–16; Reply Br. of Appellant at 4. Although the language and logic of the “extraterritorial jurisdiction” cases can be a little confusing, those decisions, as we’ll explain, aren’t really about per sonal jurisdiction at all. Accordingly, we hold that courts should analyze personal jurisdiction under the Fifth Amendment using the same basic standards and tests that apply under the Fourteenth Amendment.

We conclude that the personal-jurisdiction analysis under the Fifth Amendment is the same as that under the Fourteenth for three principal reasons.

What, though, of the “extraterritorial jurisdiction” cases that Herederos cites? In those decisions, Herederos notes, we have said that “the extraterritorial application of the law must comport with due process, meaning that the application of the law must not be arbitrary or fundamentally unfair,” United States v. Noel, 893 F.3d 1294, 1301 (11th Cir. 2018), and that the “Due Process Clause pro hibits the exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction over a defendant when it would be ‘arbitrary or fundamentally unfair,’” United States v. Baston, 818 F.3d 651, 669 (11th Cir. 2016). But a close review of those cases shows that, in fact, they aren’t really about personal jurisdiction at all; rather, at their core, they address what is sometimes called “legislative jurisdiction”—i.e., the power of Congress (or another lawmaking body, as the case may be) to reg ulate conduct extraterritorially.

Applying the minimum-contacts test here is relatively straightforward. We hold that Teck doesn’t have contacts with the United States sufficient to establish either specific or general per sonal jurisdiction over it.

For these reasons, Herederos’s suit doesn’t arise out of or relate to any of Teck’s ties with the United States. And because a relationship between the defendant’s conduct within the forum and the cause of action is necessary to exercise specific jurisdiction, the lack of any such relationship here dooms Herederos’s effort to establish specific personal jurisdiction over Teck.

Herederos hasn’t alleged facts sufficient to allow the United States courts to exercise either specific or general personal jurisdic tion over Teck.5 Accordingly, we AFFIRM.