Exxon Mobil Responds With 1,452 Pages To Cuba In Libertad Act Lawsuit: FSIA Jurisdiction Is Key

/EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION V. CORPORACION CIMEX, S.A. (Cuba), CORPRACION CIMEX, S.A. (Panama), AND UNION CUBA-PETROLEO [1:19-cv-01277; Washington DC]

Steptoe & Johnson (plaintiff)

Rabinowitz, Boudin, Standard, Krinsky & Lieberman, P.C. (defendant)

29 September 2020 Filing Links

Plaintiff’s Memorandum Of Law In Opposition To Motion To Dismiss The Action And For A Partial Stay (78 pages)

Declaration of Dr. Joan Martinez Evora (196 pages)

Declaration of Jared R. Butcher (43 pages)

Declaration of Jared R. Butcher (Exhibits 1-41) (272 pages)

Declaration of Jared R. Butcher (Exhibits 42-150) (358 pages)

Declaration of Jared R. Butcher (Exhibits 151-210) (381 pages)

Declaration of Jared R. Butcher (Exhibits 211-224) (124 pages)

Excerpts From Filing:

Congress did not intend Plaintiff’s claims to be barred by the FSIA. Section 302(c) of Title III states, “[e]xcept as provided in this chapter, provisions of Title 28 [which includes the FSIA] and the rules of the courts of the United States apply to actions under this section to the same extent as such provisions and rules apply to any other action brought under Section 1331 of title 28.” 22 U.S.C. § 6082(c)(1) (emphasis added).11 Thus, the FSIA applies only so long as it does not conflict with Title III, in which case Title III must control as Congress directed.12 Janko v. Gates, 741 F.3d 136, 139-40 (D.C. Cir. 2014). This conclusion accords with Congress’s finding that trafficking has direct effects in the U.S., 22 U.S.C. §§ 6081(2), (6), which satisfies the requirements for subject matter jurisdiction under the FSIA and the personal jurisdiction requirements of this Court. 28 U.S.C. §§ 1330(b), 1605(a)(2).

Defendants admit they are trafficking in the Confiscated Property. They admit that they use and benefit from the Confiscated Property through various commercial activities that supply Cuba’s domestic market for energy and petroleum products and that procure U.S. dollars and acquire U.S. products to sustain the Cuban economy. Measured in dollars, these commercial activities amount to billions in transactions annually. It is clear just from this introductory summary that Plaintiff has standing to bring these claims.

Defendants’ attempts to avoid liability fall flat. Their premise is that, notwithstanding sixty years of communist tyranny, Cuban entities operate independently; this is preposterous. Facing clear liability, Defendants argue sovereign immunity. But it is unavailable here for three reasons.

First, Title III expressly authorizes private civil suits in federal courts against “any person” including “any agency or instrumentality of a foreign state.” See 22 U.S.C. §§ 6023(1), (11). Title III’s exception to sovereign immunity for trafficking by state-owned entities is well founded in Congress’s findings that trafficking has direct effects on U.S. nationals in the U.S. See id. § 6081. Moreover, Congress mandated that Title III must be given priority over any potentially conflicting provisions, including the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (“FSIA”). See id. § 6082(c)(1).

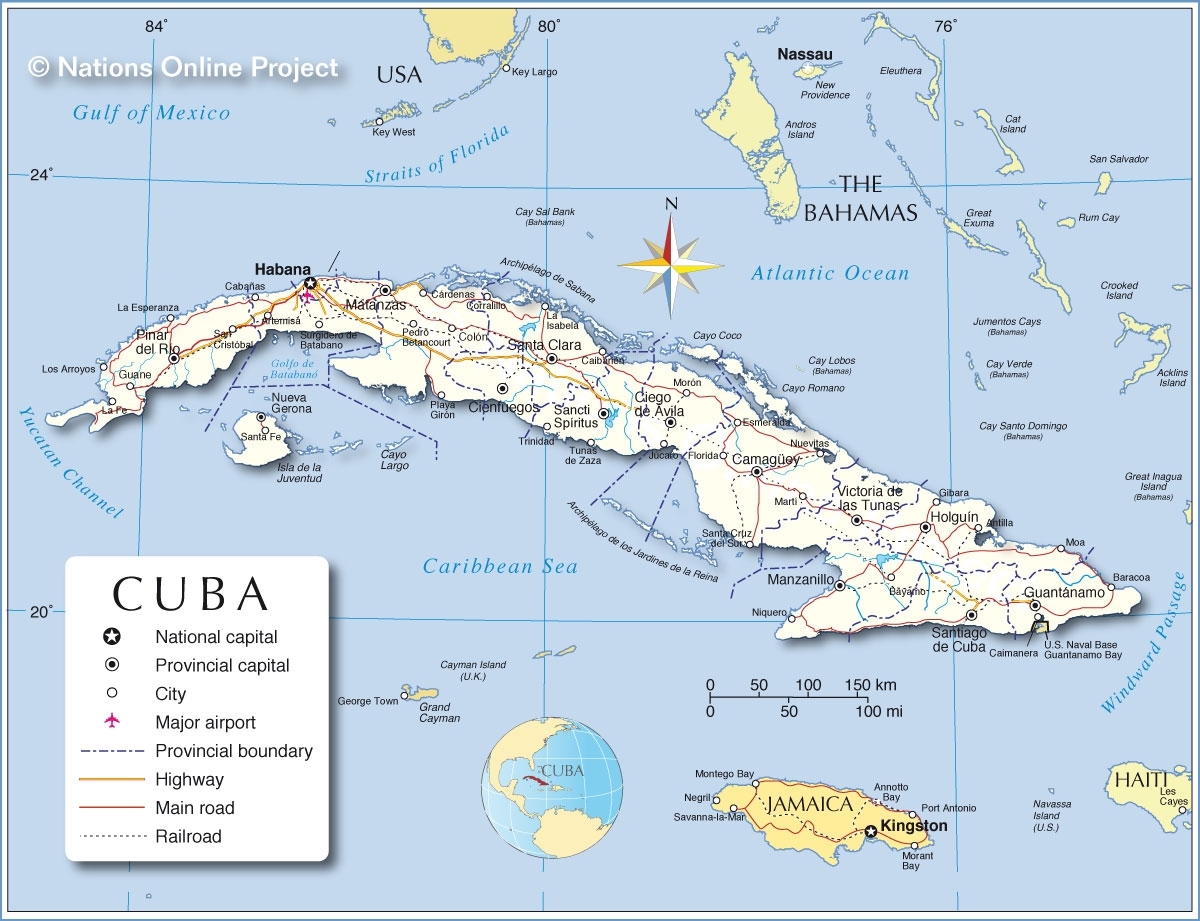

Second, even if Title III did not include an express exception to immunity (which it does), the direct effects of trafficking would satisfy the commercial activity exception under the FSIA for activities that “cause[] a direct effect in the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(2). It is undisputed that the confiscated refinery and processing facilities are used for oil exploration and production of refined products that are then sold via a network of service stations in Cuba, which includes confiscated service stations operated by CIMEX and CUPET. Additionally, CUPET uses the Confiscated Property in oil exploration joint ventures with energy companies that compete directly with Plaintiff and other U.S. companies, and CUPET admits it has travelled to the U.S. to engage in lobbying and other activities to promote and facilitate its oil exploration work.

Third, because some of Defendants’ commercial activities are conducted in the U.S., the FSIA’s expropriation exception is also satisfied. See id. § 1605(a)(3). The first requirement—that Plaintiff’s claim relates to “rights in property taken in violation of international law”—is met because Plaintiff’s claim is based on Defendants’ trafficking in property that was unlawfully expropriated. The second requirement is satisfied because that property “is owned or operated by an agency or instrumentality”—here the Defendants. And the third requirement is also satisfied because “that agency or instrumentality [the Defendants] is engaged in a commercial activity in the United States” as explained in detail below. Accordingly, Defendants’ motion to dismiss should be denied, or if necessary, jurisdictional discovery should be conducted.1

Plaintiff Exxon Mobil Corporation’s action fits squarely within the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act (“LIBERTAD”)—also known as the Helms Burton Act. LIBERTAD was essentially designed to remedy the wrongs set forth in Plaintiff’s complaint. Defendants’ efforts to deny liability are nothing more than lawyerly ploys to avoid the obvious—Defendants continue to use and enjoy Plaintiff’s confiscated property without any compensation to (or authorization from) Plaintiff for over half a century.

Page 58- Any Juridical Separateness Should Be Disregarded to Prevent Injustice

“[T]he doctrine of corporate entity, recognized generally and for most purposes, will not be regarded when to do so would work fraud or injustice.” Bancec, 462 U.S. at 629. The exception applies in cases “where a foreign sovereign intentionally seeks to gain a benefit while using the legally separate status of its instrumentality as a shield to guard against concomitant costs or risks . . . where a sovereign otherwise unjustly enriches itself through the instrumentality . . . or where a sovereign uses its instrumentality to defeat a statutory policy.” DRC, Inc., 71 F. Supp. 3d at 218.

It is undisputed that Cuba profits from the commercial activities of CUPET and CIMEX and that some of those activities involve use of Plaintiff’s Confiscated Property, which violates Title III and the policy of “deny[ing] traffickers any profits from” economic exploitation of the Confiscated Property. See 22 U.S.C. § 6081(11). Defendants are tools of the Cuban State (Evora Decl. ¶¶ 24-25), and it would be unjust to allow Cuba to benefit from the ongoing violation of U.S. laws by Defendants, while hiding behind a façade of juridical separateness.

Page 59- Regardless, Defendants Have Minimum Contacts with the United States

As discussed, Defendants have minimum contacts by virtue of their commercial activities involving the U.S. and U.S. entities. Supra Section III(B)(2)(b). Personal jurisdiction is conferred on this Court so long as it “is consistent with the United States Constitution and laws.” Fed R. Civ. P. 4(k)(2)(B). In this Circuit, personal jurisdiction “turns on whether a defendant has sufficient contacts with the nation as a whole to satisfy due process,” which is the case when a defendant “purposefully directed” its activities at residents of the U.S., even if there is no physical conduct in the U.S.

Page 60- Defendants’ Motion for a More Definite Statement Should Be Denied

Defendants’ one-sentence “motion” (Mot. at 60) is insufficient to support a motion. Regardless, it is unnecessary since Defendants know what property was confiscated and how it is used. See Feldman v. C.I.A., 797 F. Supp. 2d 29, 42 (D.D.C. 2011).